BENEVENTO

The Church of Santa Sophia

|

| The façade of S. Sophia and its square |

Founded by duke Arechi II immediately after his election (758) as a national Temple and votive Chapel for the Longobard people, it was somewhat significantly dedicated to Santa Sofia (Holy Wisdom), possibly upon the suggestion of Paul the Deacon so as to decumanus maximus (the present-day corso Garibaldi), constitued a sizable monastic complex which initially came under the jurisdiction of Montecassino.

|

|

Aerial view of Santa Sofia complex |

|

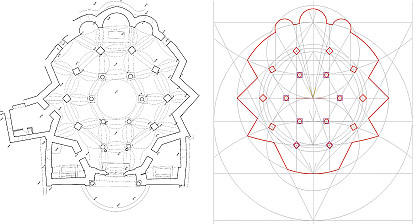

The architectural composition of the modestly-sized church (contained within a circle measuring just 23,5 metres in diameter) is of great interest. Its unique star-shaped ground plan, converging at the entrance towards the three opposite apses, must be considered an example of Longobard architecture.

THE CENTRAL PLAN

The central plan layout, probably of Byzantine influence, is highly dynamic fashion, featuring a series of innovations aimed at continually changing the internal spaces in relation to the changing perspective of the viewer. This is illustrated by the irregular progression of the outside wall, the use of a starshaped ground plan and the three relatively shallow conches. To these features are added the complex organization of interior space, with its two concentric ambulatories. The innermost of the two, marked out by an hexagonal circle of columns, describes a regular hexagon directly surmounted by the original dome, contained within a six-sloped segmental dome, positioned on a lower level than that re-built after the 1668 earthquake.

Church of S. Sophia: surveys showing the geometric generatrixes

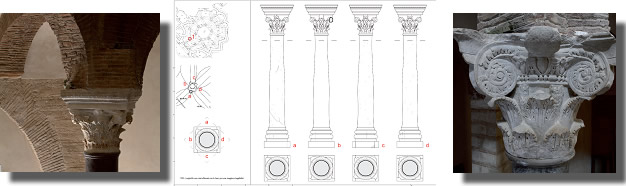

The outermost, ten-sided ambulatory is marked out by four-sided pillars which, oriented irregularly in keeping with the directional changes of the outside walls, offer excellent directional axes for an interpretation of the architectural structure. The columns of the hexagon are surmounted by capitals re-utilized from the classical period, whilst the bases are constructed using upturned and modified classical capitals, further embellished with decorative patterns.

The eight, four-sided pillars – constructed in alternate layers of limestone blocks and full brickwork – and the two columns with ancient capitals which make up the decagon, are surmounted by dosserets from the Early Middle Ages, eight of which decorated with elongated reels and pearl couples, similar to the work produced by southern Longobard goldsmiths and found in the friezes framing the sculpted scenes on the Altar of Duke Ratchis and the Baptismal Font (Tegurium) of Callixt in Cividale (providing an important link of cultural continuity between Langobardia major and minor).

Brickwork arches, partly re-built in the 18th century, offload the weight of the square, triangular and trapezoidal vaults over the two ambulatories onto the columns, pillars and zig-zag walls via shelves, set high up into the buttresses and decorated with rushes.

The large quantity of material stripped from classical sources and re-utilized in the Santa Sofia church serve structural as well as decorative purposes, as testified by the respect and consideration attributed to these relics from the past and the important uses to which they are put.

The outside walls, 95 cm thick, were realized in bordered brickwork with two rows of bricks interspersed with a row of irregularly hewn tufa blocks, visible from the outside on the south-west side and in the area around the apse. the foundations are 1,10 metre deep and wide and follow the exact line of the building’s upper walls.

The façade shows baroque influences, mirroring the configuration given to the whole building over the years following the 1668 earthquake, and features a joined gable with a slightly curved peak. The central section of the façade, including the entrance, preserves part of the four-sided structure added in the 18th century, with its exquisite doorway having marble door posts and lintels, surmounted by a lunette embellished with beautiful sculptures in high relief on a gilded background.

THE FRESCOES AND THE BENEVENTAN PAINTING

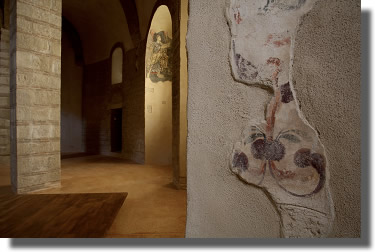

The intrados of the arches positioned to the side of the main doorway bear testimony to painted decorations which, under Longobard construction, would have covered the entire outer hangings or possibly the walls of a porch or narthex; decorations such as these typically featured semi-circular leaf patterns, partially overlapping and coloured in parts and representing a variant of a pattern popular during imperial roman times and late antiquity, yet rarely used during the middle ages.

Fragment of fresco

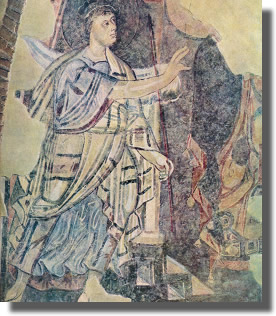

The church interior must have been frescoed in its entirety, as suggested by the fragments still visible today in the apses as well as on one of the pillars, at the feet of the segmental dome and on the pointed edges of the star-shaped walls. The frescoes found on the apse walls are one of the most important but also most controversial evidences of Longobardard work in southern Italy. The original cycle, as suggested by the scenes surviving today, ,would have focused on episodes from the life of Christ, more precisely his Incarnation and Childhood. In the eastern section of the Church, in the three little apses, certain scenes have been preserved which, although only fragmentary, bear testimony to Longobard workmanship of the highest standard. In the north little apse is a depiction of the Annunciation to Zaccharia, father of John the Baptist. The scene is split into two episodes: on the left we have the archangel Gabriel, his arm extended forwards and his hand positioned as if giving word, announcing news of his paternity to Zaccharia, of whom we only catch a glimpse of part of his heavy cloak due to a vast gaping hole in the fresco.

|

|

Left apse’s fresco. |

Left apse’s fresco. Annunciation to Zaccharia |

On the right, Zaccharia, dumbstruck by the incredible news given him by the angel, points to his mouth before the faithful gathered in front of the temple.

The stories of Zaccharia, extremely uncommon in western iconographic representations, follow the text of the first chapter of the Gospel of Luke word for word, with the frescoes illustrating many of the narrated details: the angel appearing to Zaccharia, standing and to the right of the incense altar, and the faithful looking on in wonder with Zaccharia gesturing to make himself understood. Even the clothes of the Beneventan Zaccharia are perfectly in keeping with the description given in the gospel, and although the lower hem of his cloak lacks the pomegranates it does feature at least five bells.

Right apse’s fresco. Visitation, Elisabeth and the Madonna

In the southern little apse are depictions of episodes from the Annunciation and the Visitation.

These also keep to the exact chronological order of the Gospel and the resulting cycle provides an accurate illustrated narration of the first chapter of Luke.

The scene of the visitation is highly original, its strong interpretation both affectionate and realistic.

Whilst in the past scholars did not agree over the dating of the Santa Sofia frescoes, widespread opinion now places them in the 8th century, thus dating back to the same period as the building’s construction. Agreement over the frescoes’ dating has granted “Beneventan painting” a role within the context of an artistic movement of great significance, one including the important monastic centres of Montecassino and San Vincenzo in Volturno.

Santa Sofia represents an “artistic episode able to transform the prototypes of Hellenistic learning into an existential truth” (Bologna), along with decisive Syrian-Palestinian influences introduced by eastern monks, exiled as a result of iconoclastic persecution.