SPOLETO

Basilica of S. Salvatore

The Basilica of San Salvatore is a martyrial Church for the ethnic Longobard civitas of Spoleto and it’s also an early architectural evidence of the Longobard period which expressed the ideologies of the power élites and became a model for wide range religious architecture in the Middle Ages.

|

|

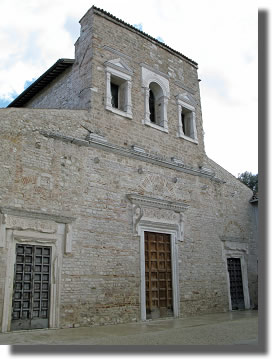

| The Basilica of San Salvatore and its façade | |

The Longobard building is the original fruit of different trends combined: Roman-Hellenistic, Byzantine, Longobard, local. Therefore the Basilica of San Salvatore was the early incarnation of cultural pluralism, which was the hallmark of the Early Middle Ages in all its expressions and would become the underlying principle of Medieval Europe.

It bears also witness to an extraordinary use of old spolia.

- THE ARCHITECTURAL STRUCTURE

- THE PRESBYTERY

- THE FAÇADE

- RE-USE OF THE SPOLIA

- RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL REFERENCES

- SOURCE OF STUDY AND INSPIRATION

THE ARCHITECTURAL STRUCTURE

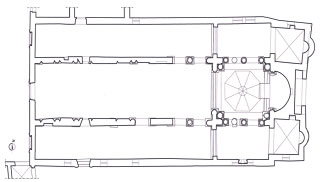

San Salvatore is a three-nave basilica with a tripartite, raised presbytery ending with a semi-circular apse and two ambulatories with apsidioles on the sides.

|

|

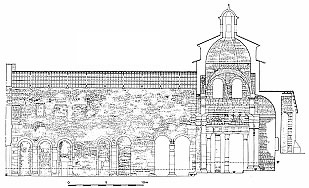

| San Salvatore, plant | San Salvatore, survey (from Jäggi, 1998) |

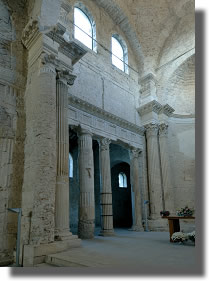

The fabric of the building was originally characterised by two architraved colonnades of Doric order, eight reused columns and two semi-columns leaning against the walls that continued in the presbytery with columns of Corinthian order, in conformity with the great western early christian architectures, from the first San Pietro to Santa Maria Maggiore.

|

|

| Nave and interior view | |

The original layout has now significantly changed owing to interventions carried out in the Middle Ages, which led to the suppression of the Doric entablature and the construction of arches. A new row of supports was then created following this pattern: two columns – a pier – a column – a pier – a column.

From the 1946 excavations by Ward Perkins, it resulted that the building, in its initial phase, should have shown a rectangular plan and only later the apse and the chapels were added to the presbytery. The investigations clarified the context of the transversal foundations of the façade, the triumphal arch and of the apse’s cord, as well as of the stylobates of the nave and the presbytery, whilst they highlighted the later insertion of the foundations of the corner columns of the presbytery.

The central canopy also refers to this second phase. It’s made of four big columns of ionic order, with entablature and soprassestoes, originally sustaining a cross vault instead of the current dome.

THE PRESBYTERY

Capitols and columns of the presbytery are made of re-used materials, whereas the dies of soprassestoes were especially created to support the cross vault; similarly, plinths and skirts beneath the Attic bases were created with reused materials so that capitols could achieve the same height as the supports of the triumphal arch.

|

|

| Presbytery | Detail of angular columns |

On each side of the apse there are two ambulatories with apsidioles, which today are actual chapels. Initially, however, the apsidioles functioned as a Pastophorium, or as the Prothesis and Diaconicon of syriac basilicas of the fifth and sixth centuries (see the church of Zenobia), ancillary spaces that held the baptistery and the relics of martyrs.

On the exterior, the presbytery is enclosed by a straight wall. Some radical re-arrangement interventions in the presbytery area were a turning point in the history of the building and aligned it with the most popular architectures in the Aegeanarea of the Mediterranean sea starting from the second half of the 6th century, as shown by the “extra muros” basilica of Korykos in Cilicia or the church of Santa Tecla in Meriammlik, whereas the three-cell layout has a Syriac origin like the peculiar tower-shaped structure that defines and tops the central portion of the presbytery. It can be found, for instance, in the convent church of Alahan Kilisè with its cross tower and, in general, in buildings containing the relics of martyrs as a specific architectural solution opposed to the Byzantine tradition of domed basilicas.

|

|

| Left side of presbytery | Chapel on right side |

Today, the original architectural ornamentation partly survives in good state of conservation, also thanks to recent restoration works.

The entablature with Doric frieze and Corinthian cornice that run above the epistyle is still partly visible in the presbytery together with a part of the overlying decoration system with false matroneum delimitated by small squarepiers crowned by ionic-like capitals, probably decorated with stuccoes and paintings. Traces of stuccoes still survive in the architrave of the main portal. certain elements in the pictorial ornamentation are preserved in the apse.

Details of architectural elements on the left side

On the central niche is a bejewelled cross from whose arms small chains with the letters A and Ω hang -entirely similar to those on the apse of the Clitunno Tempietto - and flanked by marble panels enclosing clipei.

A source dating back to the 10th century also mentions the presence of mosaics. The building’s walls are made of coloured limestone blocks and inserted bricks, whilst the upper portions of the façade and apse are made of large blocks of travertine limestone (“sponga” stone).

FAÇADE

The marble encrustations of the façade and the complex as a whole, resulting from the re-use of spolia, are particularly noteworthy. Part of the ornamentation is missing from the façade, which was originally subdivided by pilaster strips that rested on a horizontal cornice, dividing the elevation into two stories topped by a pediment. Of that decoration, three portals survive, topped by an architrave.

A classicising frame surrounds the doorways while the wide entablature is topped by a protruding cornice, under which two brackets curl up in volutes.

|

|

| Detail of the windows | Façade portals |

The three windows are enclosed by small fluted piers, raised on high pedestals and with foliate capitals. Simple triangular pediments top the lateral windows, while a round-headed arch with a remarkable cornice surmounts the central window.

The cornice is partly carved out of the stone facing that must have originally extended across the entire upper story of the façade. On the three doorframes is the same motif of acanthus foliate friezes with rosettes, rosebuds and leaves that emerge from a central stem on which the foliate cross is implanted. the sequence of fronds is enclosed into a cornice with a “leaf and counter-leaf” pattern that curves laterally.

The resulting space between the cornices and the end of the marble slab is filled by half a palmette.

On the central window, the crowning of the arch is a motif with short rays in bas-relief; at the centre, a cross takes the place of one of the rays, and the ends of the halo of rays are enclosed by two half palmettes similar to those in the portal friezes.

Detail of the main portal architrave

The sculpted parts of the façade - except for the posts and the architrave of the main portal, the small pediments of the lateral windows and the stringcourses, which are all in italic marble - are carved out of a very compact white limestone. In the course of the restoration campaign of 1997, it was observed that several of the sculpted elements were carved out of blocks pilfered from buildings of classical antiquity: on the ledge of the left window, for example, runs the inscription “AVO MATRI;” the architrave of the main portal, decorated in the visible part by a “diplex,” was part of a frame that was used as a doorsill.

Main portal architrave detail

The frieze was sculpted on the great monolithic slab of a roman tomb dating to the first century A.D. the backside of the frieze became visible when some parts of the entablature were dismantled: coffers that include rosettes ornament it, while the central portrait of the deceased has been chipped away.

The same study campaign has shown how the lack of architectural elements in the upper story of the façade (pilasters and capitals) is not due to a destructive event, as some scholars have suggested, but rather to the interruption of construction work: the bases and cornices that are still in situ, in fact, do not bear traces of manipulation - the same can be said of the missing doorposts.

Finally, the façade must have been designed with a portico in front of it: it was never built, but sculpted brackets intended for the portico are still in place.

RE-USE OF THE SPOLIA

A peculiar characteristic of San Salvatore is the consistent presence of spolia, which wereeither reused as found - for example, in the case of columns, bases, capitals, or the interior architrave - or radically manipulated specially in the decorative elements of the façade, the cornice of the presbytery and in the dies that are the dome imposts. scholars have rightly underlined the evident artistic intentionality in the reuse of spolia.

That is an indication that links the extraordinary master marble workers of San Salvatore with those of the Clitunno Tempietto.

RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL REFERENCES

The Basilica emblematically expresses the character of the Longobards’ culture in Italy, particularly the leaning towards the use of local, eastern-monastic or Roman traditions and workers to build unique products unmatched in later periods.

Its composite structures and decorations do not prevail over the uniqueness and organic unity of this place of worship which established itself as a rare evidence of a society which, in its cultural specificity, was bound to disappear with the arrival of the carolingians (with the exception of the Duchy of Benevento).

|

|

| Apse. Frescoes | |

The Longobards’ capability to acquire and reformulate structures and stylistic features of the cultures, with which they more or less directly dealt, also enabled the transmission of aspects peculiar to local traditions, which otherwise would get lost.

For example, a number of marks peculiar to the church of San Salvatore namely the taste of the architectural decoration of the façade, the type of themes used and some architectural solutions alien to the Western tradition (pastophors) are all signs of the influence of the Syrian-monastic culture.

SOURCE OF STUDY AND INSPIRATION

The church of San Salvatore - and similary the Clitunno Tempietto - were popular in later centuries as well. In the Renaissance they almost became object of interest and study.

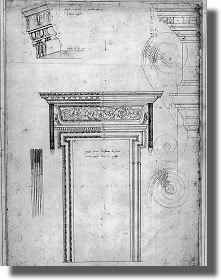

The first evidence known is still a drawing by Francesco di Giorgio from Siena dating back to the 1470, followed by the drawings of the Tempietto and an incomplete drawing of the jamb including a part of the lintel of the main and most studied door of San Salvatore by Antonio di Sangallo the Younger.

The Basilica was also the source of inspiration of Michele Sanmicheli who produced a number of works in Verona including the front door of his house, the door of Pellegrini’s Chapel in San Bernardino in 1536-37, the side openings of Porta Palio, the door of the Madonna della Campagna).

In 16th century Sebastiano Serlio, in its architectural treatise, book 4, provided a simplified drawing of the main portal, defining it as part of a heathen temple.

|

|

| Drawing of the main portal (Andrea Palladio) |

Drawing of the presbytery (Francesco di Giorgio Martini) |

The same portal was reproduced by Andrea Palladio at first in a scrupulous drawing now kept in the royal institute of British Architects in London, and later in the building of the door, anterefectory and interior cornices of the refectory of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, and the northern side door of the Dome of Vicenza.