BENEVENTO

Buffer Zone

The Longobard town occupied a smaller area than the Roman city of Beneventum thus causing the previously inhabited areas to the east and north of the present historical centre to be abandoned. The city was surrounded by a wall, large tracts of which were probably preexisting but which, given the destruction suffered during the Greek-Gothic wars, was rebuilt and strengthened.

In the 8th century, Arechis II was responsible for much new building in the city. He was aware of the importance of the Duchy of Benevento following the collapse of the Longobard kingdoms in the north of Italy and promoted the construction of many monumental works to enhance the capital of the Duchy.

Among the first constructions sponsored by Arechis II is the Church of Saint Sophia, one of the most important religious monuments of Longobard civilisation which, together with its Cloister, constitute the candidate Site. It is included in the route of the first Longobard city wall which more or less coincides with the limits of the proposed buffer zone.

THE CITY

The urban formation in the Longobard period to a large extent preserved the layout of the roman city with two main decumans oriented an E-W direction, more or less identifiable with the axis of Corso Dante/Corso Garibaldi which centrally cuts the entire historic centre in an E-W direction, and the route of Via S. Filippo/Via Annunziata to the South.

The main poles of political and religious power were within the city walls. First of all, the seat of the Dukes, located since the 6th Century in the present-day Piazza Piano di Corte which was extended and renovated by Arechis II to whom tradition attributes the construction of the sacrum palatium.

According to another theory, the palace was erected in the area of the Rocca dei Rettori, near the Church of San Salvatore, identifiable with the Palatine Chapel.

Strolling through the lanes and squares of the historic centre you can easily come across inscriptions, funeral sculptures, Roman architecture incorporated in the façades of houses or inside courtyards, or in other constructions such as the little bridges or arches connecting facing buildings.

The so-called arch of San Gennaro and the bridges of Via Francesco Pacca, one of which in opus caementicium with a lining of bricks and support arches in tuff blocks alternated with bricks, best testifies to the transmittal of Roman building techniques.

The bridges were built to connect houses, fabricae solariatae, on different sides of the same street. They were, however, built with authorisation from the sovereign powers and under the obligation to preserve the public nature of the street.

Re-use of ancient buildings and monuments during the Lombard period is well documented; the Roman theatre was intensely used as a dwelling place from late ancient times onwards.

There must also have been areas for craftsmen within the town, given the numerous activities described in literary documents (coppersmiths, cobblers, carpenters, joiners, stone cutters, goldsmiths) and the presence of mills along the banks of the river Sabato.

Recent excavations near the Museum of Sannio have unearthed a plant for crafting glass, operative between the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century. We must also remember the important illuminated manuscripts produced in the scriptoria of the monasteries, particularly at St. Sophia.

It’s interesting that the Churches of S. Stefano, San Gennaro and San Nazzaro de Iudeca bear witness to the presence of communities of eastern origin residing in the city.

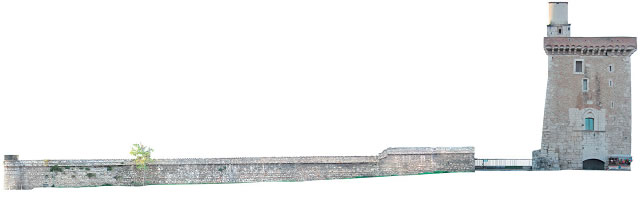

THE WALLS

At the end of the 6th century, at the time when the Benevento Duchy was being constituted, the Longobards rebuilt the Roman wall to include the hill to the east where the ducal seat, or court, was constructed, the “Piano di Corte”.

The main poles of political and religious power were situated within the city walls: firstly the ducal residence, possibly located from the 6th century onwards in today’s Piazza Piano di Corte, which was extended and renovated by Duke Arechi II, also attributed with commissioning the sacrum palatium.

A short distance away lies the Church of St. Sophia, also commissioned by Duke Arechi II between 758 and 760 A.C.

This first defensive work, aimed at rectifying the destruction wreaked by Totila during the Greek-Gothic war, excluded the south-western part of the Roman city. It is a work of fortification carried out with emergency materials and techniques, with no regular wall device and extensive use of looted Roman marble. The fortification had numerous doorways of which Porta Somma, included in the Rocca dei Rettori (Fort of the Rectors), is an example, together with the Arch of Trajan, which was incorporated in the wall and took the name of Porta Aurea.

A second Roman arch, the Sacrament Arch, was incorporated in the city wall in the 6th century. This arch was erected in the 2nd Century A.D. along the road which leads from the lower part of the city to the area of the Forum. The arch, currently undergoing restoration, was flanked by two pentagonal towers of which only one remains.

Under the government of Arechis II (758-787) the new quarter which developed in the southern part of the city towards the Via Appia, the so-called civitas nova, determined expansion of the wall towards the south, and built with more regular and precise techniques.

ROCCA DEI RETTORI OR FORT OF THE RECTORS

A short distance from the Church of St. Sophia to the south-east is the Rocca dei Rettori, built in 1321 as the seat of the papal Rectors.

The imposing building, which re-uses a large number of exquisitely fashioned Roman sculptures and architectural elements, was founded on a fortress dating back to Longobard times.

Recent excavations have unearthed some parts of the fort and part of a polygon-shaped tower that can be seen in the garden.

The settlement stratification in this area goes back at least to the orientalising and archaic era (burial sites dating to between the end of the 8th and the 6th Centuries B.C.), with important evidence of the Sannite period (fortification works with earth mounds and walls in calcareous blocks) and the Roman period (aqueduct from the time of Augustus).

CHURCH OF SAN SALVATORE

A little more to the west, behind the Palace of the Prefect, is the Church of San Salvatore, built in the Early Middle Ages and identified by several scholars as the Palatine Chapel of the court of the Longobard duchy.

Recent excavations carried out during restructuring works have allowed construction of the building to be dated at the 8th century and to unearth several burial sites from the Longobard period.

Among these is a tomb with frescoed walls belonging to the presbyter Auderisius as seen from the inscription painted on one of the long sides of the tomb. Apart from a small tassels were found inside the tomb, the only remains of the precious garments worn by the deceased.

The importance of this burial place lies above all in its pictoric decoration comprising, besides the inscription, two red, white and yellow crosses that reveal the status of the deceased person. There are very few painted tombs from the Longobard period. One of the most famous is that of the Abbess Ariperga at Pavia in the church of the ex-Monastery of San Felice.

CHURCH OF SAN MARCO DEI SABARIANI

A short distance from the Arch of Trajan in a south-east direction, in Piazzetta Sabariani the crypt of the ancient Church of San Marco dei Sabariani was recently brought to light. This church was destroyed by an earthquake in 1688 and then rebuilt elsewhere.

Another recent discovery has been made in the Crypt of the Church of San Marco dei Sabariani, where the oldest paintings, dating to the Early Middle Ages, have greatly enriched our documentation of the Longobard era in Benevento, along with the well-preserved paintings in the Church of Santa Sophia and the Cathedral crypt.

An examination of the paintings has recently been started and, for the time being, it is possible to state only that the scenes depict the lives of the Saints or, in any case, scenes from the Holy Scriptures.

The interest in this discovery has induced the Municipal Authorities, in agreement with the Superintendencies, to prepare a restoration project that will leave the building uncovered and open to the public.

THE CATHEDRAL

Destroyed during bombing in 1943, the Cathedral has preserved its splendid façade and bell tower from the Romanic period, and the famous bronze door decorated with carved panels.

The building is currently undergoing archaeological investigations resulting in much interesting information covering a vast chronological period from prehistoric times to the present.

From the Longobard period, part of a building has been discovered with three naves and a semicircular apse, perhaps part of the church that was extended between 825 and 829 by the Longobard Prince Sicone. In the crypt of the cathedral there are frescoes from the Early Middle Ages one of which depicts the Benevento bishop, Saint Barbato.

Recent excavations carried out under the flooring of the Cathedral have brought to light remains from the building’s early christian phase, renovated in the Longobard period. The three-naved building had a porticoed area near the entrance that can be identified with the paradisus referred to in literary sources – which was the burial place for the more representative personages of the Longobard community.

This gave rise to the funerary epigraphs for princes Sicone and Radelchi, and the latter’s wide Caretruda, as well as Bishop David. Recent investigation of this area has brought to light the tomb of a child, with gold thread for the clothing and a silver astylar cross that can be dated to the 6th 7th century.

The Crypt of the Cathedral, preserving frescoes from the Early Middle Ages (one depicting the Bishop, St. Barbatus), must originally have constituted a place of worship in itself..

The project currently in progress foresees entry to the adjacent Diocesan Museum, then to the Cathedral Crypt, through the Church of Saint Bartholomew decorated with frescoes and containing the remains of a beautiful floor in cosmatesco style.

The setting-up of a large historical-archaeological-monumental complex open to the public between Piazza Orsini, Via Carlo Torre and Vicolo San Gaetano, including an underground route to the Cathedral where the archaeological structures emerging from the excavations will be visible, will certainly represent a major attraction in Benevento in the immediate future.

CHURCH OF SANT’ILARIO AT PORTA AUREA

The Church of Sant’Ilario at Porta Aurea constitutes a significant example of Longobard religious architecture and is situated in an area immediately outside the so-called Longobard walls, opposite the Triumphal Arch of Emperor Trajan.

The Church has been the object of systematic investigations, conservation and enhancement work. A series of stucco fragments belonging to the church decoration are being studied in view of their possible re-placing in the building.

In recent years highly profitable work has been carried out regarding knowledge of the Longobards, relating to the legacy they have left in the architecture, urban development, painting, sculpture and even in the field of jewellery, in spite of the fact that in this sector studies have merely reconsidered objects casually found between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

THE ARCH OF TRAJAN

It is one of the most significant examples of Roman artistic culture. It was built in 114 A.D. to celebrate the inauguration of the Via Traiana, an alternative route, constructed by Trajan, to link Rome and Brindisi and faster than the old Via Appia. This road, defined by ancient historians as the “regina viarum”, the “noblest of roads”, has profoundly affected the history of his area highlighting its strategic role and the central position of Benevento.

It has also left important traces in the area and the city itself, such as the Ponte Leproso, which with its arches still crosses the waters of the River Sabato.

Over the centuries travellers, merchants, armies and pilgrims have journeyed along the Appia: under the Longobards, it was the main route from Benevento to the shrine of St. Michael at Mount Gargano and, for this reason, was known as the via Sacra Langobardorum.

BURIALS

From Late Antiquity onwards, the presence of burial sites within an urban setting marks a distinct break with the customs of roman times.

Single tombs and groups of tombs found both inside and outside the town, such as that found in Pezzapiana to the north of the present-day historical centre, or those found in the area of the Museum of Sannio and the Rocca dei Rettori, can be traced back to the Longobard period. Numerous prestigious items such as gold jewellery and armour have been found testifying to the high status of the deceased.

A gold seal ring bearing the initials AVTO has recently been found and which must surely have belonged to an important member of the ducal court. It is the only example in the south of Italy of a type of object found in northern Langobardia.

The high level reached by the Longobard community of Benevento is also seen by the painted tomb of the presbyter Auderisius, found in the Church of San Salvatore, representing one of the few examples of frescoed burial places in southern Longobardia.

Apart from those found in the centre of the town, during the Longobard period other religious buildings were located outside the city along important routes of communication. Examples of this are the monastery of St. Sophia at Ponticello and the Church of St. Hilary at Port’Aurea, situated immediately outside the city along the Via Traiana in front of the Arch of the same name.

The ecclesia vocabulo Sancti Ylari is an important example of Longobard architecture. The building comprises an apsidal hall founded between the end of the 7th and the first half of the 8th Century on imposing Roman structures. It must have been richly decorated originally as can be seen from the finely crafted stuccoes recovered during the excavation works.

These works also unearthed buildings and burial places belonging to the medieval monastery, referred to in documents starting from 1148, that developed outside the Church.