CAMPELLO SUL CLITUNNO

Clitunno Tempietto

The CLITUNNO TEMPIETTO represents a remarkable manifestation of the heterogeneous culture of the Longobard age. The components of the extraordinary cultural tradition of Spoleto are perceivable in its palimpsest.

This is one of the rare examples of monument epigraphs of the Early Middle Ages; the practice of placing monument inscriptions on the façade of a building had been abandoned in late antiquity and was not re-introduced until the 14th century when Leon Battista Alberti created one for the Malatesta Temple in Rimini.

The general style of the Tempietto, and the extraordinarily classicizing aspect constituted by reused materials and ornamentation designed and executed for the project suggest that the patrons were members of the ducal family, proclaiming their social status by connecting themselves to the grandeur of Rome.

- THE TWO PHASES

- THE SPOLIA

- A COMPLEX LANGUAGE

- THE EPIGRAPHY

- ANALOGIES WITH THE SANCTUARY OF MONTE SANT’ANGELO

THE TWO PHASES

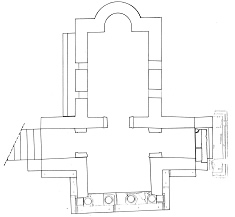

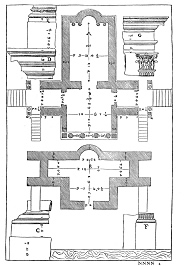

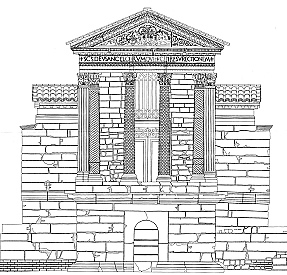

Originally, the Tempietto must have been a single room covered by a barrel vault, now the cella of the temple. An Ionic frame, pilfered from an ancient building, surrounds a door on the west wall. Five camber windows pierce the lateral walls, and a small terrace gave access to the room.

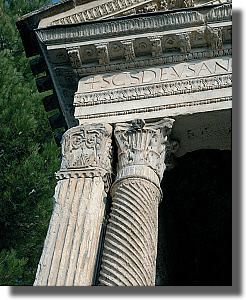

Subsequently, the terrace was enlarged to form a vestibule, and two lateral porticoes were raised on a high podium with a base and cornice. At the centre of the podium is an aperture with a Corinthian colonnade in antis, topped by ionic entablature and a pediment. Access to the terrace occurred through two flights of stairs on the side of each portico, reproducing on a smaller scale the architecture of the main building, now the only structure surviving in situ.

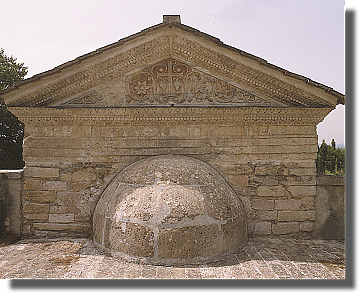

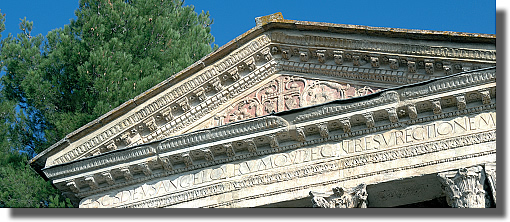

The second building phase also included construction of the apse: the back wall was demolished to raise a new one equipped with the apse. A pediment, similar in ornament to that on the façade, was also raised. Both pediments are marked by a motif of acanthus tendrils from which a foliated and apicated Latin cross emerges, with grapes hanging from the arms.

The pediment over the external apse

An entablature running continuously around the monument has the evident purpose oftying together the new parts of the building to the original construction. A shed roof covered the main building as well as the entrance porticoes.

THE SPOLIA

All of the columns are spolia, which are also abundantly present in the brick wall, in the pavement, in the cornices and architectural ornamentation of the cella, especially in the marble aedicula.

The careful reuse of spolia to create uniformity and regularity belongs to the tradition of reuse in Theodoric’s age, but also indicates an abundant availability of typologically homogenous material from ancient buildings.

The four pediments surmounting the two doors (now lost), the facade and the back wall (both in situ), were new elements produced for the building according to a unified design, with a standard motif of acanthus foliate fronds.

Detail of the tympanum surmounting the apse

The motif stems from the classical tradition but appears continuously throughout the Late Antiquity, the Early Middle Ages and the full-blown Middle Ages, in the Ellenistic Orient, the Roman-Ellenistic East world, the Byzantine world, the Roman West, the Goth West and over. The lasting presence of the motif, even if christianised through the insertion of the chrismon - the leafed tree of life dating to Constantine - is scarcely characteristic of a specific period. Dating based on formal observations is thus not secure -as the varying periods to which the building has been assigned show.

Only through an exhaustive analysis of the building will a firm dating be possible. Such an analysis will have to include a series of characteristic cultural elements: from the reuse of ancient material, in both the functional and symbolic sense, to structural and decorative practices, as well as worship traditions. In other words, it will be necessary to reflect on Longobard patronage and look closely at the culture of the period one very permeable to cultural stimuli and the influence of local traditional building practices.

A COMPLEX LANGUAGE

The Tempietto embodies a complex language comprising a series of strata, from ancient roman to Syrian-monasticism, not excluding an indigenous component.

Detail of the figure of Apostle depicted in the apse

For example, the frescoes in the cella that Valentino pace attributes to the 7th century, confirming Jäggi’s dating, are related to the roman context.

They represent the Christ Pantocrator in the apse conch, flanked by the Apostles Peter and Paul on the sides of the aedicula protruding from the apse. A velum with floral motifs fills the space below, while palms decorate the side walls of the apse. Above the tympanum surmounting the apse conch are three symmetrically disposed clipei; the central one, known from copies, is only barely discernible but is similar to the image in the apse niche of the Basilica of San Salvatore; it encloses a bejewelled cross, flanked by the apocalyptic letters A and Ω.

The lateral clipei frame two haloed angels. A ‘falsa cortina’ motif - incised lines that simulate brickwork - covers both the interior and exterior sides of the cella walls. A homogenous layer of plaster covers the walls of the cella and of the rooms within the podium —a feature that indicates, together with the stylistic uniformity of the pictorial decoration, a single phase of the whole painting complex.

The extraordinary marble aedicula on the back wall of the cella, however, dates to the Augustan age: it was dismantled from its original site and adapted to fit the apse. The masters that carried out the work carefully cut the architectural ornamentation, mounting the pieces back together so as to minimize cuts and caesuras. They polished off the work by adding three slabs in the spaces that had been created between the arch and the tympanum surmounting it. The central slab includes a clipeus with Christ’s monogram surrounded by a vegetal motif that continues over the other two slabs, and is similar to the motif on the external pediments.

The motif persisted until the full-blown Middle Ages in the area of Spoleto. Prominent examples are in the architectural reliefs of San Salvatore; more common ones are in the small pediment, now lost, of the pieve, or Parish church, of Sant’Angelo, or in the architrave of Santa Maria Assunta, the cathedral of Spoleto.

THE EPIGRAPHY

Finally, the epigraphy is a remarkable component of the monument. the famous dedicatory inscription of the tempietto still runs along the trabeation of the façade pediment:

(SCS DEUS ANGELORUM QUI FECIT RESURRECTIONEM).

two inscriptions on the lateral accesses are known from 16th and 17th century copies:

SCS DEUS

PROFETARUM QUI FECIT REDENTIONEM;

and SCS DEUS APOSTOLORUM QUI FECIT

REMISSIONEM.

Recently, the “dual soul of the monumental inscription” has been pointed out. On the one hand, it is in line with the epigraphy of the Longobard capital, marked by tall, narrow letters; on the other, an antiquarian tendency is clearly perceived. The dualism reflects the ideological choices of Longobard ruling elites, such as those of Theodoric’s age, who sought to legitimize their power through recourse to the prestige of Antiquity.

Further, on the frescoes depicting Saints Peter and Paul, numerous graffiti represent names of Longobard origin-pointing to the popularity of the site, and the intention of the devotees who visited it and practiced its cults, to leave a mark of their presence.

ANALOGIES WITH THE SANCTUARY OF MONTE SANT’ANGELO

The concurrent presence of significative elements such as:

- a) a therapeutic tradition connected to the waters,

- b) the dedication to the angels, whose cult started precisely in connection to miraculous waters-

- c) the existence of a sort of grotto - partly made out of the podium and partly cut in the rock - with cavities that seem destined to the collection of water,