BRESCIA

Church of San Salvatore

The Church of San Salvatore constitutes one of the most important surviving examples of early medieval religious architecture still standing. Recent investigations (1989) have helped shed light on the monument’s many building phases.

The Church of San Salvatore

BUILDING PHASES

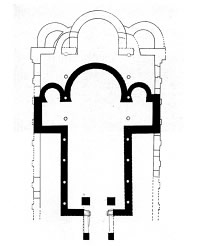

A first Longobard place of worship, dating to the second half of the 7th century A.D., and consisting of a building with a T-shaped plan, has been identified in the area formerly occupied by roman housing. This first Church shows a single-aisle plan, with a three-apsed transept, according to an architectural type which was diffuse in the area between the Adriatic and the Alps.

|

|

| Planimetry of the first phase of Longobard church |

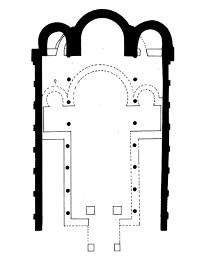

Planimetry of the Desiderius’ Church |

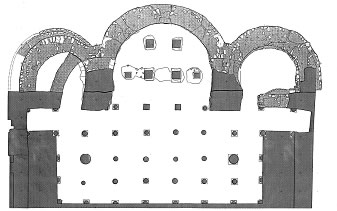

Plan of the crypt showing the romanesque enlargement

The many different architectural phases identified in this first Church point to continual use up to the mid 8th century, when the Church of Desiderius was built.

Under Desiderius the Church is rebuilt, on a larger scale, and divided into three naves by lines of columns. The widespread re-use of classical and Byzantine materials in these structures provides one of the most significant indications of the Longobards’ self-asserting stance

.

Columns and capitals are made of different materials and show different types of decorations, but are placed so as to create a correspondence of type between the ones placed in the North aisle and the ones to the South; some are elements looted from older buildings, while others were purposely created. In the northern aisle two particular “bread basket” style capitals of Byzantine origin stand out. These may have come from Ravenna, following that city’s conquest by the Longobards.

San Salvatore, one of the two “bread basket”

style capitals of Byzantine origin, re-used in colonnade

The Basilica was built by the royal couple, King Desiderius and Queen Ansa, and was entirely covered in stucco and fresco decorations, which formed a completely integrated whole; together with the decorative program of the so-called Tempietto Longobardo, in Cividale del Friuli, San Salvatore’s decoration is one of the richest and best preserved examples from the Early Middle Ages.

|

|

| San Salvatore, southern side of southern Cloister | Graphic reconstruction of Longobard building |

THE CRIPT

After the arrival of the relics of Saint Julia in year 761, a crypt was added, which later was the focus of a number of transformations in the antique period and during the romanesque period, when it was enlarged

westwards.

During the earliest phase the crypt had a semicircular shape; the space was articulated by pilasters supporting small arches decorated with stuccoes and frescoes. On the end wall was a fresco showing three framed areas, surrounded by garlands.

|

|

| Romanesque widening of the crypt of San Salvatore | Crypt. Longobard period structures |

Access to this underground area was gained by means of two annular corridors, probably equipped with wooden stairs, which led to the lower area where the sacred relics were kept.

The original decoration in the crypt probably comprised of many stucco figures, only one of which survives to this day.

PAINTINGS

Three tiers of paintings were executed on the walls of the central aisle, in the areas over the arches. The scenes of the upper section represent episodes from the life of Christ, ranging from Infancy to Resurrection; the lower section shows scenes from the lives of the saintly Christian martyrs Giulia, Pistis, Elpis and Agape, whose relics were removed from the catacombs in Rome by order of Astulf, and presented to the convent, and it was here they were placed in the crypt.

The scenes are separated by egg-and-dart mouldings, and ended in a frame painted to suggest corbels and illusionistic small arches, while busts of saints placed in round clipea are painted in the archivolts.

Frescoes’ detail of the south wall of the central nave

The cycle began in the upper section of the north wall with the scene of the Annunciation, which was followed by the journey to Bethlehem; it probably then included the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi (or perhaps the Baptism of Jesus), ending with two unidentified miracles, possibly including the miracle of the woman suffering from long term bleeding.

The stories from the life of Christ must have continued on the opposite wall, where they included events from the Passion and to his Glory.

In the lower section of the south wall it is possible to identify the burial of a saint in a sarcophagus and a number of citizens leaving a city, while a woman seems about to be taken away against her will; this last figure might be Saint Julia, being taken out of the city of Carthage.

Detail of the painted, including the name "DesiDeriuM"

At the base of these stories there used to be inscriptions, which survive only in fragments; on the south wall of the central nave the words “REGNANTEM DESIDERIUM” can be clearly read, while other lettering remains obscure.

The surviving fragments of the fresco decoration – especially on the southern wall – show landscape scenes and views of complex architectural structures, executed with a sense for the three-dimensional in lively colours, employing an original style which is however firmly based in the 8th and 9th century painting tradition of northern Italy and of the Alpine area, and which displays an interesting proximity with the frescoes of Castelseprio.

These paintings were carried out upon a very thin layer of plaster, using colours dissolved in lime over underdrawings executed with a paintbrush dipped in black pigment, having previously puckered the white plaster which served as a base. In some cases researchers have noticed a difference between the preparatory drawing and the final painted version.

STUCCOES

The stuccoes played a fundamental role in the basilica’s decorations, as they completed both the architecture and the narrative paintings, and thus followed models established in Ravenna (at Sant’Apollinare in Classe), and in Rome (at the church outside the walls, Saint Paul). Moreover, the stuccoes masked discrepancies in the joints between different architectural elements and completed the lacunae of the ancient marble re-used in the Church.

|

|

| Stucco decoration on northern wall of southern nave | Detail of stucco decoration |

The different motifs carried out in stucco (entwined ribbons, spiralling acanthus leaves, stylized lilies alternating with leaves, entwined arches, frames including ovals and reels, rosettes, cross-shaped lilies and rose shaped patterns), are placed in carefully symmetrical patterns along the intrados of the arches, the arch-rings and the aureole surrounding the faces of the main characters depicted in the frescoes. As in the friezes present in the so-called “Tempietto Longobardo” in Cividale, here too the floral elements were enhanced by small coloured glass ampoules placed in the centre of the flowers’ petals.

the coffering decoration of the flat wooden ceilings was also covered in stucco.

The stuccoes were modelled directly onto the wall, using an underlying structure made of very thin reeds, and creating the stuccoes out of many superimposed layers; the first layer was applied at the same time as the fresco decoration and the modelling was then completed and enlivened by applying pigments.

San Salvatore. Fragments of the original terracotta decoration

The Basilica of Desiderius was further enriched by ledges, corbels and small panels modelled in terracotta, the only known example of this type of artwork to have been produced at this time. These works were produced using a mould, or sculpted after firing with vegetal motifs which refer to religious themes, such as the grape vine; the absence of any works comparable to these make it difficult to make any hypothesis as to their function.

MARBLE

The ornamental motifs on the marble liturgical furnishings match the wealth of stucco and terracotta decorations; many elements have survived. Two slabs of white marble might have belonged to an ambo (a type of raised structure similar to a pulpit); the marble consistency shows a medium type of grain, and the bas relief represents two peacocks placed sideways converging towards the centre, one of the most exquisite examples of early Medieval sculpture, providing a synthesis between the naturalism of the Late Antique period and Byzantine elegance.

|

|

| White marble ambo slab showing a peacock | Arc shaped slab with geometrical and vegetal motifs probably originally belonging to a ciborium |

Arc shaped slabs with geometrical and vegetal decorations should perhaps constitute a canopy shaped structure over an altar or a reliquary, while many arc shaped frames seem to have originally belonged to a pergula or screen, separating the apse area from the Church nave.

Finally, many small columns decorated with relief decorations and capitals bearing similar ornamentation, strongly resembling the stuccoes in the basilica come from the monastery’s cloisters; these works exemplify the organic overall decorative program which included the structures linked to the Church as well as the Church itself.

BURIALS

In the main supporting wall to the South of the Church a place had been adapted to house a privileged tomb, which must have consisted in a sarcophagus of stone slabs, now lost; only its surmounting arch bearing traces of fresco decoration survives. Up to the 17th century the inscription ANSA REGINA, REGIS DESIDERII UXOR could be read on it.

|

|

| Roman Theatre. Longobard burial | S.Salvatore central nave. The 3 Early Middle-Ages burials existing under the floor |

This, and the tomb’s exalted location, in a location normally reserved to the founder, as well as the traditional offering of pies and wine to the poor to mark the anniversary of queen Ansa’s death, which is attested in frescoes on the sustaining walls beneath the intrados of the arched recess, all leads to the supposition that this may have been the final resting place of the wife of Desiderius.

Opposite the arcosolium, under the floor, there are also three burials consisting in oblong masonry tombs of the capuchin type, (i.e., consisting of a line of tiles set out to support the body, and two other lines of tiles placed so as to form a simple roof over the body itself ), their interiors decorated by painted crosses and interlaced patterns. These burials probably belonged to members of Queen Ansa’s family, possibly to her father and to her two brothers, as historical sources indicate the three were buried in the church of San Salvatore.