Scientific Area » Longobard Culture » Integration and Assimilation

« Back

INTEGRATION AND ASSIMILATION

Integration and assimilation are both processes which clearly describe the origin of the progressive evolution of the official building activity. In Longobard Italy it dates back to the half of 7th century, when the edict of Rothari (643) and the Memoratorio de mercedes commacinorum – traced back to the period of Grimoald (663-665) or Liutprand (712-744) - mentioned Comacine masters, a guild of master masons working according to the Roman tradition.

The promotion of building activities using stone and bricks by Germanic leaders, accustomed to a poor architecture of perishable materials, marked the beginning of the transformation process affecting the ancient culture which led to the acquisition of written law, the conversion to official Christianity and, in every day life, the use of official clothes made of gold brocade, jewels and fibulas (brooches) of Byzantine production or tradition.

Such processes, in different times and ways, characterized all the peoples settled in Western Europe after long migrations, but the assimilation process by the gens Langobardorum was different, unique.

The long transition process, marked by constant military operations aimed at stopping invasions and frontier crossings by barbarians in bordering imperial lands, stood out for the acculturation and mutual imitation of traditions also determined by both the presence of soldiers of heterogeneous Germanic origins in the imperial army and the ascent of warriors, titled vir magnificus and illustris, to the high ranks of the army and senate; which marked the tradition of the Longobard aristocracy (e.g. the signet rings discovered in the sepulchres of Trezzo d’Adda), with profound similarities to Byzantine Italy.

The dyphtic of magister militum Stilicho (late 4th /early 5th centuries) described the Vandal commander in his capacity as a consul, proved by the rich military clothes, the cloak clipped on his shoulder by a cross-shaped fibula peculiar to high ranking imperial officials and his sumptuous parade arms.

In 4th-5th century the cross-border Germanic élites were also affected by the process of cultural osmosis with the Roman culture which led, for example, to burials of luxuriously dressed bodies lavishly equipped with arms and bijous, fruits of gifts or trade, and to change the death ritual which, in the Early Middle Ages, marked tribes and groups of nobles migrating. The objects discovered testify changes of (mainly female) clothing due to the attraction to Roman imperial customs and fashion.

|

|

| Niederstotzingen (Germany) | Isola Rizza |

The assimilation process, the subject of a number of past and current historical debates and studies, characterized –with slightly differentiated periodizations and different outcomes - Avars, Bavarii, Thuringi, Merovingians and Longobards referred to, according to recent studies, as gentes with a multiethnic character, associated by the “awareness of being a community built on the belief of common origins and on their cohesion around a king or a charismatic leader. The Origo gentis Langobardorum, as to the Longobards, is a qualified example.

The integration and assimilation processes developed in Longobard Italy above all in the middle of 7th century, when they reached the apex mainly in palace building (almost unknown due to the scarceness and the fragmentary nature of the evidence kept) as well as in defensive and religious building, that is in architecture, which had no bearing on the Longobards before their invasion of Italy.

|

|

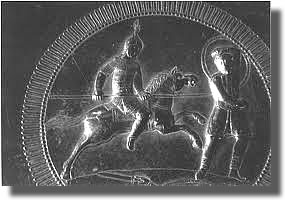

The differences noticed in the various forms of assimilations are due to the characteristics of the invaded land: the Langobardia Major, hinged on Pavia and on the duchies of Turin, Brescia, Verona and Cividale, kept a closer bond with the original tradition which is tangible in funeral gold crosses, signet rings, parade shields decorated with bronze thin plates, although it created new forms particularly in the art of wrought metals.

The Langobardia Minor, because of the inevitabile contact with the Roman Byzantine civilization, acquired more directly decoration techniques and forms peculiar to the Mediterranean tradition (e.g. disc-shaped filigree fibulas, mounted cameos and old cornelians).

However, the circulation of models and styles was constant, followed the Roman tradition and sometimes involved peripherical lands, where, though, a native tradition survived which was less courtly than the imperial one.

The official and courtly Longobard architecture (buildings of worship, monasteries and rich houses) is traced back by most experts to the half of 7th century: this was the main sign of the complete assimilation and transformation of Roman models and building techniques, as testified by the Edict of Rothari and the Memoratorium. The rural and urban landscape would, however, continue to be marked over the following centuries by poor houses and buildings made up, partially or completely, of wood, dirt floor and straw and/or reused materials.

Under Catholic king Cunipert (688-700) an important breakthrough occurred in the politics between the Longobards and the papacy. Pavia, the capital of the kingdom, became the hub of a very active evangelization of those Longobard not yet converted.

« Back